[This first edition of this review was originally published at Give Me Some Light. To be among the first to read Overstreet’s reviews, become a subscriber!]

One cinephile at Letterboxd calls The Quiet Girl “a much darker, slower, and, well, QUIETER version of Anne of Green Gables.”

I wouldn’t have thought of that, but I like it. Just as L. M. Montgomery’s novel follows an orphan girl’s coming of age, The Quiet Girl is about a young girl who begins — or, rather, begins again — to figure out how the world works, and what her part in it might be, in the context of a volunteer family.

And yes, it is darker.

This Anne — her name is Cáit, and she’s played with an angelic luminosity by newcomer Catherine Clinch — isn’t so much an orphan as a victim of abuse, abuse that culminates when she is sent away to live with relatives. We don’t see Cáit beaten or molested, although her wounded silences could suggest that either might have occurred behind closed doors. We see that both parents misunderstand her withdrawn and almost-wordless state. We see that her father (Michael Patric) is a compulsive gambler, an irascible drunk, an adulterer, and a terrible farmer who is destroying the family with his darkness and lies. We see that her mother (Kate Nic Chonaonaigh) is exhausted, traumatized, and pregnant with yet another child that the family cannot support.

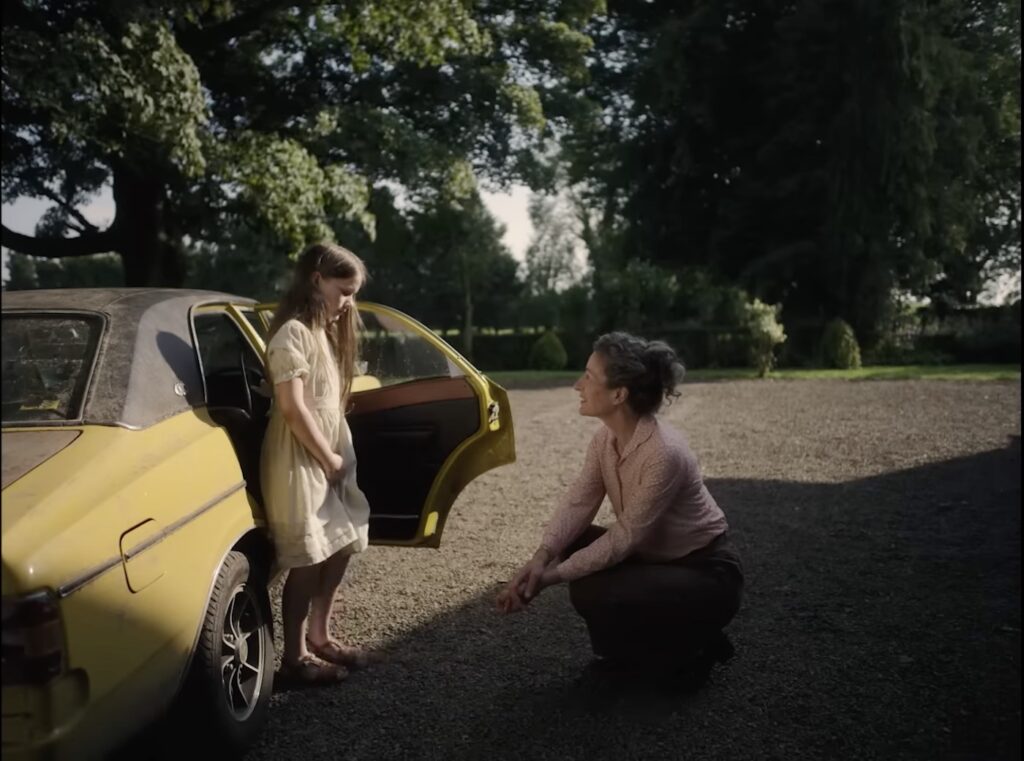

Whatever the nature of Cáit’s sufferings, she is the one that the family chooses to cast off first in their accelerating downward spiral. She lands with the Cinnsealachs (pronounced “Kinsellas”) — her mother’s first cousin Eibhlín (Claire Crowley) and her silent-type husband Seán (Andrew Bennett) — who are well-off by comparison, and who live together in an attractive but strangely haunted house. And by “haunted,” I don’t mean what you might think. This house may have a mysterious stillness at its heart, but isn’t haunted like those manors of gothic horror that so often become the furnaces in which the young children of our imaginations burn. This one is Edenic, infused with light and enchantment such that we might wonder if the Cinnsealachs’ generosity and grace have brought the property itself alive with gratitude. And Cáit responds as if she is a rare and exotic flower that has been shriveling up in a dark basement and is suddenly transported to her ideal place in the garden — her roots drink up the grace with a desperate thirst, and then her eyes open wide, her downcast countenance lifting and turning toward light as if toward some Higher Power. As she is loved, and as she begins to discover a larger world of possibility, she begins to find her voice.

I admit that I had assumed this was a story about a girl who doesn’t speak, one who would probably find her voice at the movie’s emotional climax. That isn’t, thank goodness, the case! Cáit has plenty to say throughout. This is, instead, a movie about the extraordinary power of people who have the patience and generosity to listen to the soft-spoken, the uncertain, and the insecure. And in that, it offers us one of the rarest cinematic wonders: a celebration of how children can flourish in an ideal environment, rather than yet another portrayal of how they suffer in nightmarish conditions. How many movies have been made in what feels like a lament over terrible childhoods? Those are necessary and powerful testimonies. But portrayals of any plausible possibility of goodness are so rare in art that we need to seize, lift up, and celebrate them when we find them.

Another way in which this story differs from that beloved Montgomery classic — unlike Anne of Green Gables, The Quiet Girl might work well as a stage play with a cast of only a few actors. Cáit isn’t destined to become a plucky and influential player in a community of recurring and engaging characters. Oh, the Cinnsealachs have visitors on occasion — Seán has his drinking buddies who stop by for a round of cards, and Eibhlín shines with the benevolence of a guardian angel in her community of older women. But we glimpse only a few other children in the area, and they seem like undisciplined beasts by comparison. For the most part, Cáit is on her own, a studious observer whether indoors or outdoors. Her conflict is mostly interior: She’s torn between two worlds. Should she go back to the hell where her siblings remain? Or remain in this heaven-on-earth tended by this aging and childless couple (one of whom is even “quieter” than she is)?

But then again, could it work onstage at all? The strengths of director Colm Bairéad’s film are largely cinematic. It would have to develop under the direction of a particularly talented theater director who could convey to a theater audience what this film gives us through up-close observation, through eloquent silences, and through its characters’ subtle shifts in body language and expression. Cinematographer Kate McCullough does some glorious work here.

Change any of this film’s precariously balanced performances even a little and the whole thing falls apart. The needle quivers between the extremes of Too Much and Too Little, Too Melodramatic and Too Restrained, Too Sentimental and Too Harsh. That is to say, it feels — for the most part — real.

To say much more would be to disrupt your experience of the film. Suffice it to say that Bairéad choreographs some breathtakingly truthful moments, but he contrives others that feel a little too calculated. I just wish the last shot of the movie was subtler and more surprising, and that it didn’t feel so inevitable. (I’m reminded of the last shot of Close earlier this year, during which I could almost feel the filmmakers congratulating each other for achieving a solid gut-punch that would have audiences reaching for their tissues as the credits rolled.)

Still, I suspect my love for this film is more likely to increase than diminish with subsequent viewings — largely due to the cast. Claire Crowley makes Eibhlín an incandescent force of benevolence. And, as Cáit, Catherine Clinch is unnervingly convincing (if occasionally a little too angelic).

But Andrew Bennett is, for me, The Quiet Girl’s MVP. As the humble, grieving, and hard-working Farmer Seán Cinnsealach, he’s exquisitely complicated and surprising. I keep wondering how seriously I’m supposed to take the title’s inescapable similarity to another famous film about Ireland — John Ford’s The Quiet Man. Whatever the case, Seán’s character seems a different species altogether from the brawny and conventional masculinity of John Wayne. And that’s a good thing. It’s his performance that I’m eager to spend more time with. That’s the treasure among treasures in this film that I’m most eager for you to discover.

And don’t just take my word for it. It’s not often you come across high praise of this nature:

“… like a slow, gentle walk through a garden where beauty unfolds, surrounds, and ultimately overwhelms. It is good to grasp onto love, in giving and receiving—we must hold tight to it when find it, no matter how brief it may last.” — at Letterboxd, Michael Asmus

“Simple human kindness. There seems to be so little of it in the real world sometimes that when you find so much of it in a humble movie like this one, it feels like you’ve struck oil.” — at Letterboxd, Matt Singer of Screen Crush

“Roger Ebert liked to say that it was never the sad moments in movies that moved him the most, but rather when characters showed each other unexpected kindnesses. I’m wired much the same way. … It’s a delicate film of small gestures and the slow building of trust.” — at WBUR, Sean Burns

“This movie shows that anyone can thrive as long as they are shown care and attention and are considered valuable for who they are by those raising them and that chosen families can be vastly superior to biological families. … So much healing could take place in our world if all/most children were actually shown genuine, consistent love while growing up.” — at Letterboxd, Adam Graff

“… a pleasant respite from the chaos of modern society. When people long for simpler times, Colm Bairéad’s film might be what they think of. Not that the movie is free of drama, but how director Bairéad and cinematographer Kate McCullough capture these tender moments makes even instances of anguish seem comforting.” — at Boulder Weekly, Michael J. Casey