On a recommendation from my friend Joshua Wilson, co-host of the art-and-faith podcast See/Hear Brother, I took the Barnes & Noble half-off Criterion sale as an opportunity to gamble on something I haven’t seen before: Satyajit Ray’s film Devi. And I was not disappointed.

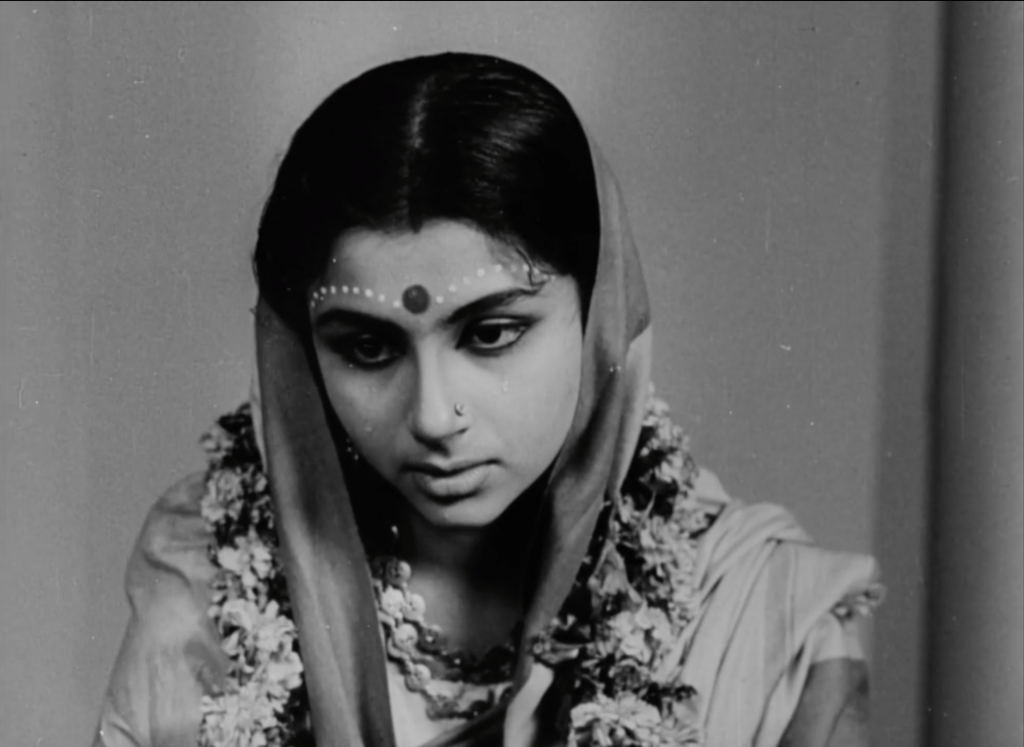

Devi, which arrived only five years after Ray’s beloved masterpiece Pather Panchali (which I wrote about here), takes place in bengal in the 19th century. We follow Doya (the dark-eyed and enchanting Sharmila Tagore), a quiet and mysterious young woman whose husband Umaprasad (Soumitra Chatterjee) is away from home to complete his studies (including studies in English). Due to his travels and his studies, Umaprasad is becoming increasingly Western in his ways of thinking, evolving into someone more rational and less superstitious than the traditional and religious community in which he grew up.

Thus he is unsettled to return home and discover that his religiously zealous father (Chhabi Biswas) has had a vision that Doya is an incarnation of the goddess Kali, and has fallen at her feet to worship her. Worse, his brother has followed suit.

Doya is now the center of a roiling storm of religious fanaticism, and their home has become a temple. People are making pilgrimages to worship her and to bring their sick to her for healing. And only Umaprasad’s sister-in-law, skeptical and jealous, shares his doubts

Does Doya believe all of this madness? Is it too late to turn back this tide of seeming hysteria?

Here’s a movie that’s 61 years old, in a language I don’t speak, from a culture quite foreign to me, in which a man realizes the waves of death and destruction that can spread when “the faithful” choose to reject the great gifts of science and medicine in healing the sick and instead rely on “thoughts and prayers.”

Better to watch something timely, relevant, and relatable, huh?

Seriously — though the film immediately immerses me in a context of religious iconography and ritual that I find unsettlingly unfamiliar, I am still drawn in by Ray’s love of reverent close-ups and his attentiveness to the intelligence and the emotions of people who speak softly and sparingly. He might have made this a movie that makes fun of the irrational extremes to which religious faith can lead its believers. But instead, by shifting back and forth between the skeptical and troubled gaze of Umaprasad, looking down at his diminutive wife at the center of a ceremonial storm, and the upward-gazing adoration of Umaprasad’s awestruck father, he draws us into the complicated silences of Doya, who is both enchanted by the waves of attention and adoration and terrified of where it all might lead.

We’re left to make up our own minds, aching for Doya in her bewilderment, sharing Umaprasad’s dread, and recognizing more than we might have anticipated about the whole scenario.

She is right to be terrified. We can feel things begin to spiral out of control, and the film’s abrupt conclusion leaves us to imagine just how much worse things will get.

This is quite a discovery for me, and one that I may write into the syllabus of my “Film & Faith” course at Seattle Pacific University. It’s rare that I buy a blu-ray of a film I’ve never seen, but something — probably my love for Pather Panchali — persuaded me that this would be worth the investment. I’m confident it will be even more rewarding in subsequent viewings, and its unanswered questions are going to haunt me for a long time to come.

For a deeper dive, read Devika Girish‘s essay for The Criterion Collection.