This review of The Quarry, the new film from director Scott Teems and co-writer Andrew Brotzman, could begin by grabbing your attention with a description of its tense and then suddenly violent opening scene. That might be a smart “hook.”

But let’s zoom in on a different scene instead, one that unfolds soon after we leave that scene of heartless cruelty:

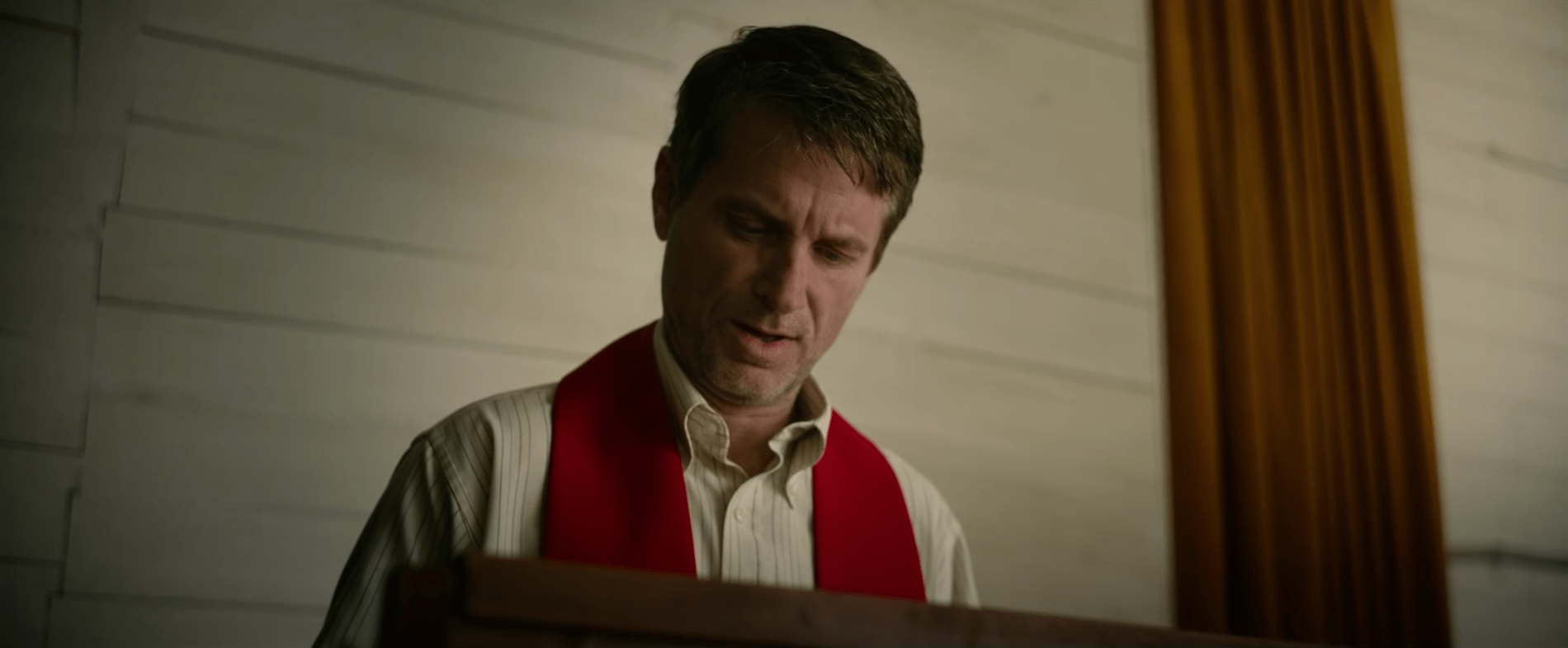

In a hush of uncertainty, a Spanish-speaking congregation gathers for worship in the small sanctuary of their depressed border-town church, eager to hear a sermon from their new shepherd, who identifies himself as Pastor Martin. To their surprise, Pastor Martin is a white man who speaks only English. They’ll need a translator. A bold woman volunteers, passing along whatever the preacher says.

But The Man — that’s what the movie’s nameless protagonist is called in the credits: “The Man” — speaks haltingly, uncertainly, staring down at his open Bible as if he’s reading a doctor’s message that he only has a few weeks to live. In fact, this stranger has no real sermon at all. All he can do is acknowledge that he is a sinner, and then read from the holy book as if seeing the words for the first time.

What his congregants don’t know is that that is exactly the case — The Man hasn’t read the Bible before. What’s more, he isn’t actually Pastor Martin, the man they’ve been waiting for. He is, in reality, a criminal on the run. And he hopes to hide the fact that they will never meet the pastor they expected.

Does anyone in town see through this con man?

Maybe. Celia (Catalina Sandino Moreno), the woman who has prepared a room for Pastor Martin, finds the man who moves in to be unlike other pastors they’ve had. He wants to keep to himself, but she’s watching closely.

Even more suspicious of the stranger is the local sheriff, Chief Moore (Michael Shannon, in simmering menace mode). Moore watches the stranger through narrowed eyes. But even if he suspects that “The Man” is actually a wanted man, he isn’t doing anything about it. Not yet, anyway. He doesn’t seem to care if the church flourishes or fails. He’s a disgruntled, world-weary lawman who scoffs at Jesus’s message of forgiveness, has a habit of sleeping with Celia, and would prefer to lock up and punish brown-skinned men from his community than inconvenience a white man.

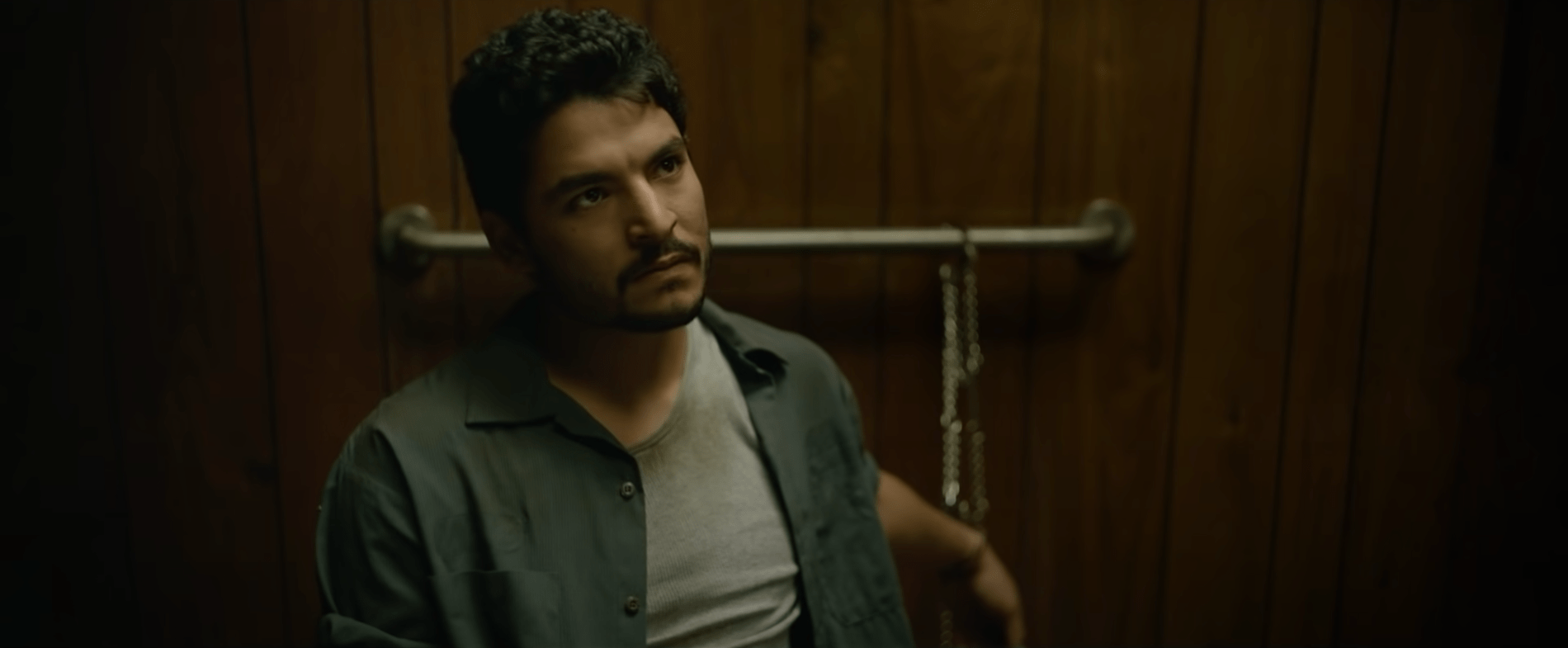

But it’s Valentin (Bobby Soto), a young Mexican-American who ranks high on the sheriff’s “Give Me a Reason to Arrest You List,” whose suspicions about the stranger are strongest. And when he ends up in jail blamed for a crime he didn’t commit, Valentin’s ready to gamble on his hunch.

Will the stranger — played with anxiety and rage by Shea Whigham — escape justice on account of the white policeman’s prejudice? Or will he be exposed as… wait, who is The Man, really?

I’m inclined to brand him with a different nickname: “The Misfit.” After all, he reminds me of the kind of troubled crook who we find wrestling with a feeble conscience in a Flannery O’Connor story. By reading the Bible aloud as a smokescreen, The Misfit ends up choking on the wisdom of the Scriptures. The Word of God surgically dismembers his falseness. And we arrive at the core of the story’s suspense: If The Misfit sustains his charade to escape the ongoing manhunt, will he be able to escape the conviction of the Gospel itself? And if not, is he capable of believing in the grace and forgiveness offered in those pages?

Whigham plays The Man like a battered old car that’s committed one too many hit-and-runs. He’s driven himself so hard that he’s either going to crash in violence, burn up with guilt, or sputter to a stop on account of emptiness. Teems, a filmmaker who has expressed admiration for the meditative cinema of Krzysztof Kieslowski, attends to The Man’s torment in close-up, but also gives us good views of the desolate territory around him, increasing our sense of his exposure and of his desperate thirst for consolation. It’s an observant (if not exactly intimate) portrait of a man who set fire to those who did him wrong, and who now has no way to escape the ongoing smolder of rage, bitterness, and guilt.

Whigham’s scenes with Shannon are the highlight of the film, as the actors work so well together, and Shannon is in his sweet spot: This performance resembles his brilliant breakout turn in Jeff Nichols’s excellent Shotgun Stories more than any role he’s played since. Their interplay suggests intriguing similarities between their characters: Moore may dress as a representative of the law, but he uses it to follow his whims, which are guided by cynicism and racism; he has no more integrity than The Man, who has at least a dawning awareness of his own wickedness.

What is the cause of Sheriff Moore’s irresponsibility and violence? In his brief rants, we learn that he is dealing with a sense of helplessness and pointlessness in the ruins of a small town, where the arrival of the Capitalism Highway stole away the town’s essential businesses — “and,” he adds, “all the nice quiet folks along with it.” He’s not content to police the poor who are left scraping out a living. His dissatisfaction manifests as an eagerness to punish anyone he perceives as a problem, and he’s not inclined to hear even a pretense of the Gospel. “Forgiveness only works in a world where people learn their lessons.” Whether he’s complaining about repeat offenders or his own uncontrollable impulses, it’s hard to say.

Moore and The Man raise some of the more challenging questions I’ve encountered at the movies in 2020. So I’m dismayed to see so many critics dismissing this film for being “slow.” By contrast, I’m drawn in to its weighty concerns. There is a lot going on here — and none of it is delivered in the typically lurid and crowd-pleasing vocabulary of sensational violence, sex, and verbal sparring. These characters have complicated interior lives and histories, and much of the drama is taking place beyond the reach of their words.

The burden of guilt, the reality of consequences, and the possibility of forgiveness: That’s the heart of the matter. But there’s another subject at hand that intrigues me even more — and that has to do with language barriers.

Celia is fond of a hymn she sings in Spanish because, even though the words don’t rhyme that way, at least that connects her to the song in a direct and personal way. Similarly, the Mexican-Americans of this town need consolation, guidance, and vision in their own language. The woman who serves as a translator, motivated by the people’s needs, is the true voice of Gospel in this desperate church. The Man himself, reading God’s word in his native English, can’t seem to “translate” these concepts of love and grace in any way that makes sense to him, even though it’s clear that he is despairing over his sins.

The film’s weighty spiritual inquiries may suggest we’re on a narrative arc toward a heart-warming redemption. But Teems and Brotzman, transplanting a story by novelist Damon Galgut from South Africa to West Texas, are braver storytellers than that.

They’re clearly working in the same world where Flannery O’Connor’s violent, jarring, difficult stories take place — a world in which characters rarely reform and, if anything, they might catch a brief epiphany regarding grace before things fall apart entirely. They’re also traveling the same roads as Cormac McCarthy’s characters from No Country for Old Men, where a reckoning for humankind’s evils is coming, and no gunslinging sheriff has what it takes to restore law and order. I am also reminded of Robert Duvall’s The Apostle, with its earnest portrait of preacher trying to reconcile his violent impulses with the Gospel he preaches, and Wim Wenders’ Paris, Texas, with its story of a seeker staggering through a wasteland in a last-ditch effort to get one thing right after a lifetime of wrong.

I was delighted to see the subtle talents of Catalina Sandino Moreno again — I frequently have students watch and write about her character in the film Paris, Je T’aime — but I wish her character had more to do in this story.

That is, in fact, the only weakness I find worth mentioning here: The film’s fleeting run-time seems to prevent us from getting to know these complicated characters better. Teems, who has done outstanding work for the TV series Rectify, directed a distinctive indie called That Evening Sun, and made a little-known but beautiful documentary portrait of Hal Holbrook in Holbrook/Twain: An American Odyssey, excels when he has time to patiently attend to explore the relationships between characters’ crises and the secrets of their histories. While The Quarry gives us glimpses of the wages of sin and the need for a hope beyond the damage of the immediate human sphere, it leaves us with a lot of room — perhaps a bit too much — to imagine where these characters come from and discuss what we might learn from them.

But the strengths of the film — its performances, its truthfulness, its thoughtfulness, its timeless relevance — far outweigh its weakness. I saw the film weeks ago, and I’m still thinking about the problem of the monster that Sheriff Moore has become, the options for Celia as she looks for a meaningful future, and The Man as he seems to have dug himself a grave and cannot now free himself from its gravity. Teems is truthful enough to show us that no confession can undo damage done, and the ground is soaked with blood of those who suffered and died for crimes the didn’t commit.

As Americans recently watched in horror as their Liar-in-Chief used violence and cruelty to clear out a church property just so he could hold up a Bible for a photo-op, perhaps the single-most iconic moment of American hypocrisy in my lifetime, we might read this film as a prophecy that we are now headed towards blood and ruin. No less a Christian visionary than J.R.R. Tolkien once wrote (in a letter to Miss J. Burn on July 26, 1956), “[O]ne must face the fact: the power of Evil in the world is not finally resistible by incarnate creatures, however ‘good’….” But then he concluded that statement with another truth: “… and the Writer of the Story is not one of us.” The story of The Quarry is unfinished when the credits roll. And I find that both frustrating and encouraging. Life is like that.