I will not mention Terrence Malick when I review As It Is In Heaven. I will not mention Terrence Malick when I review As It Is In Heaven. I will not mention Terrence Malick when I review As It Is In Heaven. I will not…

Oh, forget it.

To reference Terrence Malick in reviews of films about faith is becoming as common as referencing Flannery O’Connor in reviews of Southern fiction. But that’s the power of an artist’s vision: Malick and O’Connor both sought to reflect hard truths without flinching. Both sought to find hope by marching through — instead of around — the darkness. And in doing so, they spoke to an audience that knew darkness and was thirsty for something meaningful. They presented a picture of faith in which there were actual stakes. Both refused to accept the vocabulary of their medium, and instead expanded it, showing us things we’ve never seen before, taking risks to convey beauty and truth in new ways. And in doing so, they did something far better than “send messages” — they captured imaginations.

To reference Terrence Malick in reviews of films about faith is becoming as common as referencing Flannery O’Connor in reviews of Southern fiction. But that’s the power of an artist’s vision: Malick and O’Connor both sought to reflect hard truths without flinching. Both sought to find hope by marching through — instead of around — the darkness. And in doing so, they spoke to an audience that knew darkness and was thirsty for something meaningful. They presented a picture of faith in which there were actual stakes. Both refused to accept the vocabulary of their medium, and instead expanded it, showing us things we’ve never seen before, taking risks to convey beauty and truth in new ways. And in doing so, they did something far better than “send messages” — they captured imaginations.

Now, their artistic descendants are embracing and expanding those vocabularies.

What’s more — the best of them are going beyond imitation, and demonstrating that they have attended to and absorbed the visions and innovations of other great masters.

In the case of Joshua Overbay, the director of As It Is In Heaven, we have a unique debut that may remind audiences not only of Malick but also of Robert Bresson, Ingmar Bergman, and more recent visionaries like Jeff Nichols (Shotgun Stories, Take Shelter, Mud).

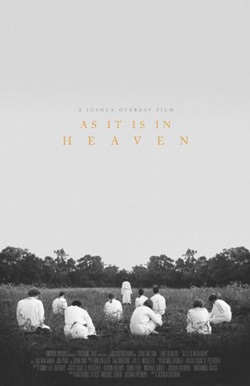

So forgive me but, yes — As It Is In Heaven, shot by Isaac Pletcher, looks a lot like a Terrence Malick film in its haunting opening shots of a woman in a white gown moving through Edenic environs toward a river where a baptism is underway.

So forgive me but, yes — As It Is In Heaven, shot by Isaac Pletcher, looks a lot like a Terrence Malick film in its haunting opening shots of a woman in a white gown moving through Edenic environs toward a river where a baptism is underway.

Behold: A kindly older man they call “The Prophet” (John Lina) is baptizing a newcomer (Chris Nelson). Around him, the followers in this Kentucky church (cult?) rejoice at the salvation of another soul. Their community is growing.

Communities of faith tend to grow bolder and more secure in their beliefs when their numbers increase. (How many pastors take congregational growth as assurance of God’s blessing and approval?) In this case, the community needs assurances. They follow a leader who sees this small sect as distinct from the rest of the church. They want to believe that they are special, that they have found the answer. They want to believe that if they obey this man, they will be delivered from a world that has hurt them, let them down, and sent them in search of an escape.

The day of reckoning, says the Prophet, is very close.

Well, he’s right about that. A day of reckoning is coming. But not the way he thinks it is.

In a turn of events so portentous that you might even call them “Biblical,” the heir apparent — Eamon (Luke Beavers), the Prophet’s only son — is passed over for this humble, reluctant stranger. The one who has been given the rather loaded name of “David.”

David seems earnest, eager to prepare the people. He wants to see them purified from sin so they will be worthy of redemption — an idea that anyone familiar with the Gospel will recognize as, well… the opposite of Jesus’s teachings, and rather like the teaching of those Jesus most firmly rebuked.

What’s remarkable is that all of these characters live within the cult. We’re not given an outsider’s perspective that will make us feel comfortable. We come to care about these people, and our hopes rest on anything that draws any of them closer to freedom, closer to truth. What’s more, we get a sense that each one has suffered some kind of alienation or severe loneliness — lacking a family or community or a sense of purpose. No wonder they might be drawn to this ready-made family, community, and purpose.

(I wonder — How often do we stop to consider what might lead other communities around the world to unite beneath the banner of some fanatical ideology? It’s so much easier just to say “They believe the wrong thing, and thus they deserve our condemnation.” Perhaps if we were stronger exemplars of our own beliefs, and showed the rewards of it to our neighbors, they would not seize upon such misguided causes, such communities where they can find a sense of belonging. But that’s a subject for another time.)

I’m tempted to argue that the cult itself just doesn’t seem very plausible. What kind of people would entrust their lives to such a mercurial, self-proclaimed “prophet”? But I watch the news. And I hear the stories. I know a lot of people who have been rattled by the collapse of a major church right here in Seattle, a church that placed far too much authority and power in the hands of one man, a man whose good intentions were not enough to make up for his misguided and legalistic ideas. Most people I know stood around saying “Why can’t these congregants see where their choices are leading them?” But that sense of satisfaction that comes from belonging to the right team, from being assured that the Right Man is doing the thinking for you, from believing that any kind of questioning or criticism is an attack… that will steer you away from the Gospel every time.

What’s more: The larger a cult becomes, the more persuasive and compelling their collective affirmation of a false prophet becomes. Who’s likely to volunteer as a nay-sayer when a barn full (or a sanctuary full) of congregants are cheering for their pastor?

What’s more: The larger a cult becomes, the more persuasive and compelling their collective affirmation of a false prophet becomes. Who’s likely to volunteer as a nay-sayer when a barn full (or a sanctuary full) of congregants are cheering for their pastor?

It would have been easy to villainize David — to make him seem insane or malevolent. The film is far more troubling because we can see David’s eagerness to be a good leader. We can see him leaning into prayer and intuition for guidance. Oh, what a little theological guidance could do for him. Oh, what a close reading of the gospels would reveal. (If you want to argue for the importance of Biblical literacy, show people this movie.)

So, seeing David’s naivete and the burden of responsibility, we’re afraid for him as his followers distrust him and question his claim of authority. But we’re afraid most for those followers who have so much to lose if they are led any farther astray. Viewers won’t forget Deb (Shannon Kathleen Baker), the mother of an infant who is commanded to deny her baby nourishment during a cult-wide fast in the name of holiness.

It would have been easy to write this off as a story of “crazy Southerners.” But Overbay is careful to make the cultists seem as if they might have come from anywhere. (As he points out in this revealing interview with Alissa Wilkinson at Christianity Today, you won’t notice Southern accents in the cult.) That makes this group seem like it might be just about anywhere, around the corner.

The film stands as a convenient refutation of the common cliche “All religions are the same.” Perhaps you remember that moment in The Polar Express when the conductor said, “The thing about trains… it doesn’t matter where they’re going. What matters is deciding to get on.” Yeah, that sounded nice, but it’s total b.s. It matters very much which train you climb on. Because trains will take you in different directions, to different destinations, on different tracks. You know how that inspiring song goes: “People get ready, there’s a train comin’, pickin’ up passengers coast to coast… And faith is the key!” Ah, but faith in what? In whom?

Does this train exist under the tyranny of law, where you must earn your salvation with good behavior? It’s a seductive idea, this notion of earning your place on a Gospel train by following the rules of the conductor. And it’s an exciting thing for a lonely, lost soul to surrender freewill, or to learn a code, in order to purchase the embrace of a community called “The Chosen” in Jesus’s name. It’s even more exciting if you’re assured salvation for your behavior.

Here’s a hint: If you find that your train’s conductor

- claims to get “words from the Lord” that directly contradict Jesus’s teaching,

- casts off the good news of God’s unconditional love and grace for a new rule of law that makes him the judge of who’s “chosen” and who isn’t,

- sets himself up as “the shepherd” and the sole arbiter of truth,

- isolates the community from outside connections,

- teaches that God will “leave the earth to rot,” and

- interprets people’s hardships as evidence that they’re hiding secret sins …

… you’re probably on the wrong train.

I prefer a vision of the Gospel I stumbled onto in Joe Henry’s Invisible Hour:

There’s a train already come,

There’s a train already come,

Her hands are birds, her heart a drum —

Lo these many years…

In other words The Kingdom of God is at hand. Don’t feel like you need to go find it. It is, as Jesus said, within you.

It may surprise some viewers to learn that there were many Christians instrumental in the making of this film. It was directed by Joshua Overbay, written by him and his wife Ginny Lee Overbay, with the support of students from a Christian school — Asbury University. And I offer them my sincere congratulations. They have refused to take the path of so-called “Christian movies” — that growing industry of movies characterized by zealous evangelism, propaganda, and (alas) a destructively dualistic view of the world.

Most films that get branded as “Christian” demonstrate a fundamental misunderstanding of how art works and what it is for. But these filmmakers? Although many of them are Christians, they show no eagerness to make a “Christian Movie” — that is, a film designed to persuade viewers to become members of a particular team. Rather, they have employed imagination and excellence in carefully composed images and a subtly crafted narrative that respects viewers’ intelligence. By inviting us into an experience rather than subjecting us to an illustrated sermon, and by demonstrating compassion for all of their characters rather than setting up a false dichotomy of “good guys” and “bad guys,” they create a space for encounters with beauty, mystery, and truth, where all kinds of good contemplation and revelation can occur.

Think of the countless hours of tedious work invested in the typical CGI-drenched Hollywood blockbuster. Then consider that this suspenseful film was shot without any special effects over the course of 17 days. This is powerful filmmaking, admirable for the resourcefulness of the artists. There is no substitute for the power of actual human beings, the actual rhythms of human relationships and dialogue, the power of silence, and the influence of actual environments in front of a camera.

Think of the countless hours of tedious work invested in the typical CGI-drenched Hollywood blockbuster. Then consider that this suspenseful film was shot without any special effects over the course of 17 days. This is powerful filmmaking, admirable for the resourcefulness of the artists. There is no substitute for the power of actual human beings, the actual rhythms of human relationships and dialogue, the power of silence, and the influence of actual environments in front of a camera.

I’m tempted to say that these filmmakers have asked us to consider how prone human beings are to desire a different Christ than the one we we’ve been given, and to reconsider what the claims of the Gospel might actually be. But no — that’s just what I find myself thinking about. The movie makes no move to preach or proselytize. Instead, it shows a path that moves in the wrong direction, so that the audience senses the deepening shadows, feels the disorientation that comes when we lose track of the sun’s true position in the sky.

In that sense, I’m tempted to say that As It Is In Heaven may have been influenced by, of all things, The Blair Witch Project. Just as that film limited our vision to what one wanderer’s handheld camera showed, cursing us to constant claustrophobia and motion-sickness in a maddeningly endless forest, so As It Is In Heaven gives in us an increasing sense of vertigo by closing us in — psychologically, communally, and spiritually.

If I have any trouble with the film at all, it’s that I suspect that life within cults is actually less stifling than this — that they discuss more than just their charismatic leader, that they talk about where they came from, what they miss, what about the world outside they might still love and covet. (I’m grateful to an insightful colleague who found the right words for this.) These characters might have come to life even more fully if the film had given us a fuller sense of their histories and interests.

But that’s quibbling. Watching As It Is In Heaven, I was never less than enthralled. As bizarre as the scenario might seem at first, it’s happening in all kinds of ways all around us. And if we’re not vigilant, it’s happening to us as well — in how we allow ourselves to be carried away by the charisma, the flattery, the promises, and visions of appealing figures like patriarchs, pop stars, pastors, presidents, CEOs, and even technological devices.

By asking these good-hearted but misguided people to make incredible sacrifices for his incomplete vision — and by limiting their environment to the houses, barns, and woods they’ve made the base of their separatist activities — the Prophet has doomed them all.

•

As It Is In Heaven is now streaming on iTunes and Vudu.

•

Looking Elsewhere

Michael Leary at Filmwell:

If Overbay can produce something so accomplished (truly, this film is marked by Overbay’s sense of nuance and precision) with so little, I am excited to see what he could put together with a bigger budget.

And I am not sure to what extent Overbay would agree, but this is Christian art in a clear, engaging, and historic sense. At times the film feels like a religious faith wrestling with its own object.

Wade Bearden at 1MoreFilmBlog:

The fact that Joshua and Ginny Lee Overbay have crafted a film that nourishes the mind and aesthetic sense of believer and atheist alike redounds to their credit. Here’s hoping the Overbays resist the temptation to pander to a niche market in subsequent films, and continue to create artful, broadly appealing movies.