This article on “Christian fantasy” by novelist Lars Walker confesses something that may surprise his readers:

I don’t read much fantasy, and I read almost no Christian fantasy. I’ve been burned too many times. You buy a book, hoping to experience over again the joys great fantasy can provide (for me, the Mines of Moria, the Ride of the Rohirrim, and the resurrection of Aslan provided the greatest moments of joy I’ve ever experienced in literature), and what do you get? Wannabees. Wannabee Tolkiens, wannabee Lewises, wannabee (christened) George R. R. Martins.

While I might have named different storytelling moments — scenes from Watership Down, The Tale of Despereaux, Winter’s Tale, along with some from The Fellowship of the Ring — I found myself nodding in agreement.

But then I came upon this surprising paragraph…

Who’s writing good Christian fantasy today? … Walter Wangerin Jr. wrote one of the best fantasies of any kind I’ve ever read, The Book of the Dun Cow, an amazing animal story that I promise will break your heart and put it together again. Stephen Lawhead is an excellent writer who has never (in my opinion) soared to the heights he’s capable of. Jeffrey Overstreet may be the best.

Wow.

I’m honored and grateful and inspired to get back to work on my new novel. I’m grateful that Walker appreciates these books so much.

Walker’s a formidable storyteller himself. His novel Wolf Time is on my nightstand right now. (I tend to read a dozen books at a time, little by little, over many months, and this is the only fantasy novel currently in the mix.) So, to be highlighted by him is a huge encouragement, and it sends me toward a weekend of writing with new enthusiasm and confidence.

Walker’s a formidable storyteller himself. His novel Wolf Time is on my nightstand right now. (I tend to read a dozen books at a time, little by little, over many months, and this is the only fantasy novel currently in the mix.) So, to be highlighted by him is a huge encouragement, and it sends me toward a weekend of writing with new enthusiasm and confidence.

However — friends, family, and those who have been reading this blog for a while probably know what I’m about to say — for the sake of preventing misunderstanding, I am duty-bound to offer a contrary opinion. I know, it feels kind of self-defeating to disagree when somebody says something complimentary about my work, especially when that somebody is more experienced and more accomplished.

But here I go anyway…

I don’t write “Christian fantasy.”

I write fantasy.

While I do have some Christian readers, I don’t write stories for a Christian audience, nor are my stories designed to deliver “Christian messages.” There is no reason for my novels to be segregated from other novels, to be branded as part of some sub-genre.

I want my stories to be held to the standards of great fantasy writing. They may fail by that standard — only time, and greater imaginations than mine, will determine that. But “make-believe” is the game I’m playing, the tradition I’m following, the goal I’m seeking to achieve.

I wouldn’t know how to write “Christian fantasy” if I tried. I don’t know what it is. I don’t see labels for “Hindu fantasy” or “Buddhist fantasy” or or “vegetarian fantasy” or “atheist fantasy” in the bookstores, and there’s a good reason for that. Art is about exploring possibilities, not fashioning messages or proselytizing. When artists start trying to “make points” or “deliver messages,” their art suffers and becomes something else.

Much of what I’m saying has been expressed here many times before, primarily in the foundational vision of this blog: “Mystery and Message,” by Michael Demkowicz. If you haven’t read it, check it out. It says a great deal in a few words.

You’re probably familiar with author Katherine Paterson. She wrote Bridge to Terabithia and Jacob Have I Loved. In a Books and Culture interview, she once said,

Novelists write out of their deepest selves. Whatever is there in them comes out willy-nilly, and it is not a conscious act on their part. If I were to consciously say, ‘This book shall now be a Christian book,’ then the act would become conscious and not out of myself. It would either be a very peculiar thing to do–like saying, ‘I shall now be humble’–or it would be simple propaganda…

Propaganda occurs when a writer is directly trying to persuade, and in that sense, propaganda is not bad. … But persuasion is not story, and when you try to make a story out of persuasion then you’ve done something wrong to the story. You’ve violated the essence of what a story is.

I don’t have the stature of Paterson. I am not one of the great fantasy writers of the world. But that’s not something I worry about. When artists concern themselves with their own greatness, they’re in trouble. I want to focus the energy and time I’m given differently. I want to discover stories that are unfamiliar, that wrestle with questions that are new and challenging for me. I’m focused on developing characters I find interesting, so I can follow them.

And I trust that if I pay attention and work hard, they will lead me to all kinds of truth, all kinds of beauty.

My grandfather didn’t build “Christian houses” — he built spacious, sturdy, wonderful houses worth exploring. In a way, I’m doing my own work inspired by him. My stories are not “Christian stories” any more than my coffee is “Christian coffee,” and my favorite hill climbs of the Pacific Northwest are not “Christian hiking trails.” I don’t want my companions on the journey to think that we’re engaged in some kind of illustrated sermon. We’re on an adventure.

“Ah,” you might say, “but you are a Christian. Your beliefs will affect your story. So your stories will reflect truth differently than secular stories do.”

My answer to that — “No, not necessarily.” In my life of reading, moviegoing, listening to music, and studying visual art, I have encountered truth, beauty, and mystery as much in the work of non-Christians as I have in the work of Christians. I’d even go so far as to say that the truth and beauty I have found in the work of unbelievers has strengthened my faith even more than what I’ve found in “Christian art.” And that’s to be expected. I believe that we are all made in the image of God, and that eternity is written in our hearts… in all of our hearts. Thus, when anybody achieves any kind of beauty or truth in their work, that goodness is from God, whether the artist likes it or not.

I want to write stories for the whole world, stories that enchant readers with their beauty, provoke readers with their questions, haunt readers with their mysteries. I want to write stories that inspire readers to investigate important questions, rather than illustrating arguments in hopes that they’ll agree with me.

If my work is categorized as “Christian fantasy,” all kinds of trouble and misunderstanding begins. People begin to assume — wrongly — that they should be looking for religious symbolism and and allegories that I seek to avoid. They write reviews on Amazon that severely misinterpret the stories. (Many of the reviews of The Auralia Thread there, even the positive ones, make me cringe because readers have read them with only one set of lenses — lenses you use when you think that your job is to discern a religious allegory. As a result, they’ve missed out on much of what I believe these stories are about, and they ignore all kinds of details and characters and subplots that are essential to the story.)

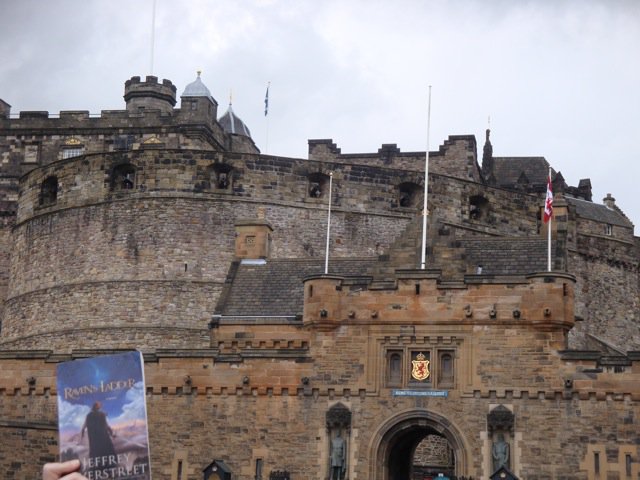

Novels by Marilynne Robinson, Leif Enger, Katherine Paterson, Wendell Berry, Madeleine L’Engle, J.K. Rowling, Walter Wangerin Jr., Tim Powers, Gene Wolfe, and J.R.R. Tolkien are shelved in Literature or Fantasy. I’m not saying my work is as accomplished as books by those great writers — Christians, all of them — but if Auralia’s Colors, Cyndere’s Midnight, Raven’s Ladder, and The Ale Boy’s Feast are branded as “Christian fiction,” they’ll remain set apart from the books that inspired them, taken away from the audience for whom I wrote them.

Even if my stories pale by comparison, they were written in the same genre as books by George R. R. Martin, Neil Gaiman, Mervyn Peake, and Patricia McKillip (writers whose stories are, by the way, filled with echoes of Christ’s teachings… whether they intended that or not).

If you were a winemaker, and you found your bottles shelved with diet soda, or vice versa, you’d be bothered, wouldn’t you? If you made a sports car, and found it advertised as a family SUV, you would suspect — correctly — that its real purpose would never be discovered or acknowledged. Further, it would greatly confuse shoppers who were looking for a family SUV.

If truth and beauty and mystery — those things that make us wonder about God and salvation and the meaning of life — are what make a book “Christian,” than I’d argue that most of the best “Christian books” were not written by Christians, and you can find them all over the bookstore, not just in the “Religion” section. Finding Nemo, WALL-E, and John Carter were all stories written by the same filmmaker — who happens to be a Christian — and all three were full of ideas and themes that Christians will celebrate. But they were not “Christian movies.”

Here’s a passage of Walker’s article that made me cheer:

How do you produce good fantasy (I won’t say great fantasy; that’s beyond my expertise)?

First of all, remember this truth—e-books make it possible to publish your own book. That does not earn you the right to expect anyone else to read it.

Writing is a craft, like shoemaking. I don’t care how sincerely the guy who made my shoes loves shoes. The main thing I want from him is expertise, the practiced knowledge of how to put together a shoe that fits, won’t give me blisters, and lasts a while. Your sincerity may please God, but He also says, “Whatever you do, work at it with all your heart, as working for the Lord, not for men” (Colossians 3:23, NIV). It’s possible you may be a prodigy, a literary Mozart capable of amazing the world right out of the gate. But probably not.

Amen to that!

That’s why I buy the best shoes I can buy. And I have never, ever, ever shopped for “Christian shoes.”

That is why you should check out Lars Walker’s fantasy novels. They are heavy, challenging fantasy stories that fans of the Inklings — and beyond — will find rewarding.

So again, sure, it’s encouraging that someone familiar with “Christian fantasy” — whatever that is — would say that he likes my work. Especially an accomplished writer like Lars Walker. But to be honest, I’m hoping that somebody somewhere will someday read them the way they read any other fairy tales or fantasy novels, find something that troubles or intrigues or haunts them, and tell their friends, “I just read the strangest fantasy series.” To deliver that — instead of something called “great Christian fiction” (as nice as that might sound) — would feel like a mission accomplished.

Praise from Caesar. Thank you. I know what you’re saying, but it seems to me the category “Christian fantasy” is kind of inevitable.

Ah, you’re singing my song. I met you at Glen West 2011 and 2012. Last year at the Glen I was in Bret Lott’s fiction workshop. He said, “Here in this place, “Christian” isn’t meant to be an adjective.” That stuck with me and continues to do so as I struggle to write my own fiction. I just returned from the CrazyHorse Writers Conference at the College of Charleston (more Bret Lott, God bless him) and was privileged to meet Patricia Hampl. We talked about this very subject. When I shared Bret’s “Christian as adjective” comment to her, she hooted out loud. None of this is new, of course, but every once in a while we need to stand up and say it again. So glad you did.

I think I agree with you for the most part, intending to write Christian fiction produces lousy fiction but the man who believes that his perspective and world philosophy doesn’t effect his fiction at all is deceiving himself. (and readers looking for symbolisms in works by Christians is foolish) So maybe I feel that you have addressed the issue lopsidedly in order to guard against one extreme. Especially since our philosophy doesn’t incorporate in building a house or making shoes. The builder and the shoemaker deal with phys ical limitations and live inside matter but novels are enfleshed ideas of the novelist, which draws on his own soul, imagination and maybe unconscious desires. He may have the limitations of grammar and work within certain limits of associations of images ( C.s. Lewis called the laws of Imagination) , within the limitations of character’s actions but it’s still going to be a vision produced more or less by our philosophy. To say Lewis and Tolkien didn’t produce Christian Fantasy seems a bit self evident. A buddhists’ heroes would be different and so would be a muslims. Truly Frodo was a hero born out a christian ideal. To say a polythiest doesn’t articulate about the world different is ridiculous. Obviously Christianity saw very different the story of Prometheus than originally intended by the greeks who produced it. Prometheus has become a story that pointed out pride because he regards his gods as small and withholding good, so he stole from them. A titan forced to suffer forever for giving man fire. The greeks intended it as a criticism on pride in the same way. It’s not in the same realm as Christ who came from a generous God. Which hero should we say would represent a deep world philosophy. Hercules or Frodo? Obviously not all fantasy is the same. Skills with words and grammar merely means the skillful enfleshment of imagination( or at least the goal).

The greeks intended it as a criticism on pride in the same way?

Corey wrote:

Thanks for commenting, Corey. (Good to hear from you!)

For what it’s worth, I never said that a man’s perspective and philosophy don’t affect his fiction. Everyone’s perspective and philosophy affects what they say, write, and do. I just don’t think Christians should be singled out for “labeling” because of it.

Corey wrote:

Ah, but I think that the craftsman’s work is also influenced by imagination, values, and convictions. It may not be as easy to point out the results in, say, a pair of shoes. But if we were to consider the how and the why of the craftsman’s work and business, it would become more clear. Further, I do think that a person’s beliefs affect their material work, sometimes in large and obvious ways, sometimes in small and subtle ways. This has never been more clear than today, as more and more scrutiny is given to business practices, labor laws, and standards of quality and excellence.

Corey wrote:

I didn’t say that “a polytheist doesn’t articulate about the world” differently. But I don’t think that, in the marketplace, a polytheist’s work should be categorized separately as Polytheist Yogurt or Polytheist Saxophone Music or Polytheist Fairy Tales.

Furthermore, atheist and agnostic storytellers, in their ventures to tell good stories, end up reflecting the themes of the Gospel all of the time. It would probably bother them if we pointed that out. But… case in point… look at the film Pan’s Labyrinth, which Guillermo Del Toro made in order to celebrate the “pagan fairy tales” he had loved as a child, and which he made *instead* of making “The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe.” (He wouldn’t make Lewis’s story into a movie because he didn’t want to make a movie with Christian themes.) Well, guess what? “Pan’s Labyrinth” told such a good story that I heard from all kinds of people saying that it was a beautiful picture of… yes… the Gospel.

I think it would be difficult to call anything polythiests fiction. I think it’s too general of a description. There are different kinds of polythiests…. I would say hindus would be in that realm….. my point is that we label things all the time Jeff. We label them by their philosophical bent or as a description. We label things as stoic, post modern or even puritan ( and we won’t even discuss style labels) . I think the greatest difficulty that comes with describing something as Christian fiction is that the word has been used as an Umbrella for so many things that are not Christianity….. Like Jesus says not all of those who are jews are of Jerusalem…. (However Christian fiction is not ” Monothiestic fiction” , obviously it’s more specific. ) I would say jesus’ parables had a universal appeal, but there are few that require jewish eyes and understanding(the parable of the cunning manager for one requires some middle eastern ideas)and a bit of Jewish history knowledge Not an absolute requirement but it leaves a greater impact on those with a jewish empathy or perspective. To say some of Jesus’ parable were “Jewish” would seem very accurate being that he was discussing the Kingdom of God. I think N.T. Wright and Eugene Peterson point out the Jewishness of Jesus’ parables. They can definitely be describe as jewish parables to a samartian crowd at least in Luke. My point is that calling something Christian fiction maybe a bit of a hastily thrown out label that people place unconcernedly but there is justification to say that Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings would at the least be referred to as Christian fiction. Not because it was meant just for Christians but because of the philosophy of the writer that shaped it and the fact that those who are Christians are more keenly aware ( or at least should be but notice the Jews heart hearing was a bit dull) of what is being said. Christian fiction should scandalize “the Jews not of Jerusalem”. I think the issues you’ve brought up over the years about how we approach fiction by asking questions and not trying to be focused on a moral of the story is awesome. However this kind of exploration of questions are still a Christian forcing questions upon the reader that more than likely are Christian based questions. I mean your own Novels implies there is something about the pagans that might point the way to something bigger than the pagan myths( the Keeper is not God *spoiler*) . Questions like that are not harmless philosophical ponderings but earth shaking questions from a specific perspective …. Christianity. Questions about issues about war, vigilantism, revenge, love loss and so forth are just general questions but Christian produces conundrums of hope the world wonders at. Whether we want to admit it or not, Christianity offers unique questions. Christ’s parables were designed to draw out something specific in order to either repel those who weren’t following, the hard hearted know it alls and to offer a vision of something to appeal to the sinner. My point is that you’ve criticised christian fiction, redefined it in a specific way and then decide to say well it not Christian because these questions are universal. I guess we could call it Catholic then 😉

A line in Madeleine L’Engle’s ‘Walking on Water’ which has always resonated with me that I wrestle with is “If my stories are incomprehensible to Jews or Muslims or Taoists then I have failed as a Christian writer” I try to think about this in everything I do, but it’s certainly a challenge.

I have at least two book projects in the works right now, a collection of poems (a la Shel Silverstein-Dr Seuss-ian variety) and a fantasy novel. Though some of my poems have a subtle spiritual bent, most of them are just about life in general, or about funny, off-beat stories & characters. My novel is something I wrote over 14 years ago for a 3-day novel writing contest…..at the time I wrote it, I was more of a ‘new-ager’ in terms of my beliefs. But in coming to faith since then, I still have no intention of injecting any Christian “agenda” into it….I’m simply trying to do good work and tell good stories.

Hey, Jeffrey, interesting article. We’ve had discussions about this topic in the past, and as you may remember, I have a different perspective. Writing, above all, is communication–shoes aren’t. Consequently, the writer needs to have something to say.

In addition, our conscious thoughts, not just our subconscious, are ones we can and should communicate. Interestingly, more and more general market writing instructors seem to be addressing this subject. This from uber-agent Donald Maass in his most recent writing instruction book, Writing 21st Century Fiction:

“Ducking the big questions is easy. So is achieving low impact . . . Do we teach in schools ‘truths’ that are untrue? Does the accumulation of capital do good or does it corrupt? What are the limits of friendship? Should loyalty last beyond the grave? We read fiction not just for entertainment but for answers to those questions. So answer them “(pp 169-179 emphasis mine).

In addition, earlier in the book he says “Meaning itself in the form of theme is necessary for high impact” (p. 20).

Part of the reason that Christians aren’t writing great fiction today is because, no matter how much we emphasize “craft” we fall short by what we have to say. We’re not on the same page as our culture. We’re speaking past our society, answering questions they aren’t asking. We say, Jesus loves you and wants to be your Savior, to people who don’t think they need saving. We can say it with finesse or literary excellence, communicated in an engaging story, but it will not resonate with those grappling with other questions.

Jesus didn’t start out telling the woman at the well that he is the Messiah. At the same time, he didn’t hedge when it came time that she was ready to listen.

I hear two extreme attitudes expressed by Christian authors–one is the idea that our stories are to reveal Christ and the other, that our stories aren’t to have any intentional “message.”

Maass seems to disagree: “Having something to say, or something you wish us to experience, is what gives your novel power. Identify it. Make it loud. Do not be afraid of what’s burning in your heart. When it comes through on the page, you will be a true storyteller” (The Fire in Fiction, p. 249).

Should “Christian fantasy” be uniquely different from “fantasy”? As far as I’m concerned, the “Christian” adjective (and it’s just as appropriate as an adjective as is “American”) identifies the worldview from which the author is speaking. Consequently the “what he’s saying” will come from the philosophical underpinnings of Christianity. Is it bad to “tip our hand” like that? I don’t think so. In fact, a lot of readers of ebooks who didn’t know going in that they were reading a book with a “religious bent” were critical because they weren’t warned.

Say whatever you want to about the Left Behind books (I haven’t read them), but it’s clear that a good number of people who don’t normally read “Christian fiction” read those books, knowing that they were written from a Christian perspective. From that I conclude, having something to say that is distinctly Christian isn’t the problem for most novels written by Christians. We need to look deeper.

Becky

Thanks for your thoughts, Rebecca. Sometimes I think we’re closer than we think, and that a lot of our debate is largely about semantics. When you say that a writer “has something to say,” for instance, I suspect you mean something more than just an artist has a “lesson to teach.”

But in an attempt to clarify that I don’t mean, and have never said, that artists shouldn’t care about making meaningful work… I’ll divide my response into parts:

1.

You wrote:

Sure, but not all writing really qualifies as art. And my post about fiction was about art, not merely “communicating.”

Here’s an illustration…

–

A teacher looks at a tree and thinks, “That tree needs water and sun like a person needs love and friendship. Hey, I have something to say! I’m going to go tell people!”

An artist looks at the tree and says, “That tree is so beautiful, and it is saying so much to me. I want to paint a tree!”

The teacher may deliver her message successfully.

The artist may give people an encounter like their encounter with the tree, from which people may glean all kinds of wonderful “messages” … but more than that. They might see trees, or people, or the world with new eyes, due to the mysterious power of art to suggest things beyond words, beyond explanation.

–

Writing can communicate “something to say.” Art can communicate something that’s bigger than any explanation. (“Show, don’t tell,” as the famous principle goes.)

Most of my favorite artists say, consistently, that they write to “find things out,” not to convey messages or answers. Further, if I sense that an artist is trying to persuade me of something, my suspension of disbelief begins to crumble. Art is unique from other forms of communication in that it invites us to explore and consider and discover, and the greatest art gives us the distinct sense that the artist is, herself, exploring.

As the poet Cecil Day-Lewis said,

And the great Elvis Costello says,

Art gives us something that cannot be reduced to a paraphrase. Most (not all) of the stuff I’ve read that is labeled “Christian fiction” has been so eager to “deliver a message” that I’ve lost interest. And it hasn’t given me a reason to go back and read it again. There is something mysterious in the way beauty whispers about meaning beyond what we can boil down to a lesson. And the artist is one who strives for beauty, knowing that it may say much more to the audience than even she will see.

Further, even if a work of art can give us clear illustrations of truth — like the way Samwise and Frodo show us the virtues of loyalty and friendship — they do so in a way that gives us much more to think about than mere “communication” would. There is something mysterious, something worth investigating further. Every time I read The Lord of the Rings, new implications, new suggestions, deeper meanings reveal themselves. That is because the artist was dong more than merely “having something to say.” He was painting pictures, loving the details, and by refusing to simplify the story into “lessons,” he created something alive that speaks in an individual way to each reader.

A few more favorite quotes from writers and artists whose work has inspired and moved me:

“I think writers with actual intentions generally end up saying things they already thought they knew, and I’m not much interested in reducing my vocation as a poet to something like propagandist. I write poems to find things out, not to communicate some previously ossified conclusion.” – poet Scott Cairns

–

“No; we have been as usual asking the wrong question. It does not matter a hoot what the mockingbird on the chimney is singing. The real and proper question is: Why is it beautiful?” – Anne Dillard

–

“…often my father would read us things that he loved, without a word of ‘explanation.’ Of these the Ancient Mariner stands out beyond the rest. O happy living things! Why do people murder them by explanations?” – Molly Hughes, A London Child of the 1870s (1934)

–

“It may be that when we no longer know what to do we have come to our real work and that when we no longer know which way to go we have begun our real journey. The mind that is not baffled is not employed. The impeded stream is the one that sings.” — Wendell Berry, “Poetry and Marriage,” Standing by Words

–

“You will find something more in woods than in books. Trees and stones will teach you that which you can never learn from masters.” – Saint Bernard

–

“The Christian writer does not decide what would be good for the world and proceed to deliver it. Like a very doubtful Jacob, he confronts what stands in his path and wonders if he will come out of the struggle at all.”

– Flannery O’Connor

–

“But it sometimes happens that it is not the poet himself, but another, who discovers the wider relevance [of the poet’s work]. If so, he is justified in so interpreting it in the place where he finds it; for the relevance was always potentially there, and once seen and recognized it is actually there forever. This does not, of course, mean that we can read into poets anything that we jolly well like; any significance that contradicts the whole tenor of their work is obviously suspect. But it means that in a very real sense poets do sometimes write more greatly than they know; and it also means that every poet’s work enriches not only those to whom he transmits the tradition, but also all those from whom he himself derived it.” – Dorothy Sayers

–

“When we understand the outside of things, we think we have them. Yet the Lord puts his things in subdefined, suggestive shapes, yielding no satisfactory meaning to the mere intellect, but unfolding themselves to the conscience and heart.” – George Macdonald

–

“We do not draw people to Christ by loudly discrediting what they believe, by telling them how wrong they are and how right we are, but by showing them a light that is so lovely that they want with all their hearts to know the source of it.”

– Madeleine L’Engle

–

If Jesus has told parables merely because he had “something to say,” we wouldn’t have thousands of sermons on each of those parables. They present us with a problem, with a mystery, with challenges that never stop opening themselves up.

I never said writers shouldn’t “explore themes.” But a “theme” is not a “message.” We can invoke a theme and then deliver a message about it. Which is fine. We can be messengers. Or we can be artists, who invoke a theme and then hold up something beautiful, like a mirror to nature or to the world, and allow us to find truths there that mere “saying” would not sufficiently provide.

2.

You wrote:

You’re talking about a personal conversation, not a work of art.

And yet… AND YET… Jesus loves poetry so much that he cannot resist using metaphors. Why? Why not just say what he means? Because merely saying what he means isn’t big enough. Only metaphors, only poetry, will convey the Truth that is Bigger than mere Messages. And what has happened? To this day, we wrestle with what he said there. We find new nuances in it. We realize that while we have begun to understand it, we have only begun to understand it.

3.

You wrote:

Interesting. I hear a variety of attitudes.

But to reveal Christ is to reveal a mystery. He spoke in so many metaphors and parables that we will never exhaust the riches of what he had to say. Further, even his actions were mysterious and poetic… becoming the greatest story ever told.

I have never met a Christian who says that art should not have anything meaningful to express. But those who have written the stories and poems that bless me are those who turn to poetry and storytelling because they want to provide something greater than a lesson. Can I list for you a bunch of “messages” that are in my favorite stories? Sure. But if I did, that would be like pulling a few grains out of a loaf of bread. And I’m convinced that the writers were not thinking about “teaching” those “lessons” when they wrote, or the bread would have been hard and tasteless.

If my readers come away from my story saying, “I agree with that message,” then I have failed. If they come away saying, “That was beautiful,” or “That was challenging,” or “That was intriguing,” or “That was haunting,” or “That was troubling,” then the art is doing what I hoped it would do. They may indeed “learn lessons” as they think about it. But if they do, they’ll also receive new questions, and they’ll want to go back for more.

4.

As I’ve said many times before, if writers are striving to achieve beauty and truth, any truth and beauty that they achieve belongs to God and does a good work.

Because Christian storytellers often start with “a message” and then dress it up, they often end up stating some good things, but they are weak in imagination and beauty, and there stories end up only delivering those messages.

The art that has drawn me closer to Christ in my life has come from non-believers as often as from believers, perhaps even more often. Because those artists were focused on capturing something mysterious, beautiful, and true without the complication of trying to persuade. Thus, their works haunt me and stay with me in a way that a mere “illustration” does not.

5.

I’ve read Donald Maass, and he has some good things to say. But mostly I found him counseling me on how to write something engaging and entertaining, and how to write something that sells. I didn’t glean from him much that has taught me about the life of the artist, the secrets of poetry, and why the books that mean the most to me and to others are often those that did not “succeed” right away or make many people happy.

“The truth must dazzle gradually,” said a poet who really knew what she was doing. Or rather, who really knew that she could not completely know what she was doing.

^^^^^^^ I really admire this about you Jeff and why your short talk at SPU captured my imagination and my strong admiration. I hope you don’t find my comments and writing antagonistic. I just feel that Christian Fiction needs to be redefined instead of having the label thrown out. I feel when we start referring to Christian fiction as writing merely by Christians for Christians then it seems to lose itself. I don’t believe that all stories need to be “a vehicle of truth” in the sense of message. If Christian fiction is merely a moral tale then I feel that we aren’t dealing with fiction as more an instructive example like Aesops fables or a persuasive argument . Fiction should dazzle gradually but maybe that’s the definition of Christian fiction. Something the creates a haunting beauty or creates a great mystery that causes an invitation towards something greater. Bruce Lee used to refer to the finger pointing at the moon. ” If you focus on the finger you will miss all the heavenly glory”. Our joy and beauty in fiction should in the end, point to God not in some contrived manner but because of the attention and joy of creation,thde sense of hope in the very attitudes present in fiction because of the “Way” we are interested in life. You constantly use L’engle’s approach to attract non christians” to the light’, so you are attempting to use it for Kingdom means. I would call that form of fiction done by Christians, Christian fiction. The intention, worldview perspective and Spirit fruit like Joy are present as well as deeply thoughtful and well written. (not aimed just as entertainment at Christian people). However we aren’t drawing them merely towards some indefinite thing or object but to a specific person, not just a monotheistic God but God who entered the world and established his kingdom by strange means, The person of Christ. I too am thankful for the non-christians work whom God has spoken to me through. Right now i read a manga where the faithfulness of a friend in a single character seems so foolish that the other characters wonder why he constantly pursues his friend. Hosea’s commanded example of faithfulness comes to mind and provokes questions about my own faithfulness and through the manga gives me a modern way of seeing God’s persistent pursuit. However this pursuit has to be taken out from it’s philosophical web of self suffiency or burdening ourselves too much with doing everything by our own efforts ( within the Authors own fiction through his character). Am I thankful yes. So I agree with alot of what you say above….. I apologize for the long post. I also apologize for co opting this from Rebecca. I ask for forgiveness if my previous posts were a bit presumptive. I find your thoughts informing a great deal of how I think about movies and fiction and art and many of your reviews have left me enlightened and encouraged.

Footnote to my last comment (which I may have neglected to post as a reply to you, Jeffrey): I don’t think having something to say is the same thing as persuading people. But if I am to give readers something meaningful to think about, I don’t think it’s possible unless I first have thought about it myself. I may expand my views as I write, but first I have to have something I actually think is important to say. I don’t believe doing so in any way stifles the imagination.

In this regard, I wonder if we aren’t talking about writing styles (outliner or pantser, as the current shorthand seems to define it).

Becky

This post was about how the segregation of “Christian fiction” has done my work more harm than good, and how I am weary of having the “wine” I’m trying to share with the world labeled and categorized as some other kind of beverage.

On the subject of artists’ approaches to their work, there are too many paths to discuss in this thread. I am not trying to persuade you to write the way I do. If you need to come up with “something to say” before you write, go right ahead! That’s not an appealing approach to me — I’d rather explore something that I find mysterious, and make up characters and follow them to see what happens and what themes and revelations emerge — but I’m not trying to persuade you to do what I do. I would just say that there are certain commonalities in the visions of artists who inspire me, in the works of art that speak to me, and in the work I’m striving to do. And those commonalities have to do with discovery, with mystery, and with beauty… with things that cannot be reduced to “a point” or “a message” or “something to say.”

The heavens declare the glory of God. Do they have something to say? They have endless volumes of things to say, and while gazing upon them moves and inspires and heals me, I won’t be able to simply explain what they are “saying.” I want to make art that speaks through beauty and mystery the way that God’s own creation tends to do. And the only way I know to do that is to approach with humility, with the knowledge that art is full of mystery, and that the more I strive for beauty the more I am dealing with truth in a way that cannot be boiled down to an explanation.

OK, another footnote (I should have known I couldn’t give a short answer to your thoughtful comment!): You said, “An artist looks at the tree and says, ‘That tree is so beautiful, and it is saying so much to me. I want to paint a tree!’ ” This actually illustrates my point. In that instanced, I don’t think the artist would be saying anything. If, however, they said, I want to paint this tree in such a way that others may see what I see, then, yes, I’d say the artist is communicating.

Writing is communication. There’s no way around this. An author writes and a reader reads, so ideas have flowed from one person to another. If an author simply explores and doesn’t let the reader in, there’s no point to putting the work out there for the public. It belongs in a private journal.

Becky

Much of my favorite art has been painted by people who were learning about their subject by painting about it. They didn’t arrive at conclusions ahead of time… they discovered conclusions by painting. If they are doing their work with skill and beauty, then it will reflect what they discovered in the act of looking and making.

If they were not doing their art in a way that reflects what they see, then their work is going to be self-indulgent and pointless.

The more I talk to great songwriters and painters and musicians, the more I find that they can only say so much about what their work means. They were in a mysterious act of relationship, of love, when they were serving their subject. They wanted to make something beautiful and to make something out of their encounter. Sometimes what they make is to be shared, sometimes not. But if they have concerned themselves too much with making sure an audience gets a point, then they usually end up narrowing that work of art unnecessarily, and making something that feels like a lesson instead of an experience.

Rather than trying to say what they want to say, they are trying to hear what the subject is saying, and trying to capture and reflect that. In that sense, it is a humble service. The artist is not the authority, but a servant who holds a mirror and tries to offer a reflection of the view from their vantage point. How many times have I told an artist what I saw in her work, and she was surprised and delighted and said, “Wow, this is so much bigger than me. I had never thought of that before.”

I realized something when I read these lines, Jeffrey: “But if they have concerned themselves too much with making sure an audience gets a point, then they usually end up narrowing that work of art unnecessarily, and making something that feels like a lesson instead of an experience.” When I say, “have something to say” you’re interpreting that as “make sure the reader gets the point.” I think there’s a necessity for the writer to let go whether or not the reader will understand and concentrate on saying what he or she wants to say. And I agree with Maass (not talking about books that sells well)–literature that has high impact, that affects people deeply, is that which has something to say.

Great discussion–thanks for giving us much to think about

Becky

I think part of what Jeffrey is speaking against is the commercialization of fiction that caters to Christian buyers … in that sense “Christian” has (sadly) become a marketing term and nothing more.

Because this market has grown so large, the bookstores have sectioned us off into our own little corner as if we were a genre all our own, which limits our audience greatly. Rare is the Christian author published by Christian publishers who can escape that corner. (And if anyone’s books deserve to be out there and mixed in with the others, its Jeffrey’s novels.)

But let’s be honest … if any other religiously oriented segment of the population (atheist, hindu, muslim, etc.) grew as large as the “Christian” segment, it would probably be segmented off in the bookstores, too. It all comes down to marketing tactics, and our books have suffered for it, not only because of the sectioning off, but because we, as authors, are content to stay in our own market and focus so much on message that our craft has failed in many ways (mine included, but that is for others to judge).

But … don’t think that I’m saying that one shouldn’t write for the Christian market (I am myself, in general) … I just think that Jeffrey is trying to open our eyes to the possibility that “fiction as beauty, adventure, and art—in and of itself” can also glorify God, and that maybe we’ve lost that in our modern market-driven mania.

-Robert

Jeffrey, my point is simple: because someone has something to say (truth) does not preclude him from doing so in an artistic way (beauty). I feel your original post focused on beauty in such a way as to suggest that truth wasn’t important.

The act of discovery through writing that you’re talking about is fine, but that’s not the only way. Jesus wasn’t trying to discover what he believed by telling parables. He knew exactly what he believed and what point he wanted to make. Yes, as we read all of Scripture we realize his parables have greater meaning than what we may have first assumed. Depth in no way cancels out the idea that the author has something to say–it actually reinforces it. It’s pretty hard for someone less intentional, say, than Tolkien, to have the layers you referred to re. TLotR.

Hmmm. I may have to blog about all this! 😉

Becky

You wrote:

Wow. I’m re-reading my post, and I don’t see that at all. I talked about truth and beauty. And to me, the two are inseparable.

If we are making something that is truly beautiful, we are embodying truth, whether we know it or not. Facts and platitudes and messages are just the most basic, elemental building blocks of truth. What makes truth a part of our lives is when we are drawn in to engage it, wrestle with it, explore it, make it our own. When truth is powerfully embodied, its beauty becomes manifest, and the beauty of it pulls us in.

I did not even imply that truth is not important.

Nor did I ever suggest that Jesus doesn’t have “something to say.” In fact, he has so much to say, mere “lessons” and “messages” are not enough. He speaks poetically, relentlessly. The Word must become Flesh. Truth must become embodied and incarnate. If he was just “making a point” with a parable, then eventually we’d “get the point,” and we wouldn’t need the parable anymore. Truth is too mysterious and alive and beautiful to be reduced to a “point.” It needs to be embodied… in art and in action. Sure, we can learn lessons from his storytelling, but that’s just the beginning. His stories are also mysterious, and they keep us coming back to discover new layers of meaning because they are more than just “points.”

An artist might start with “a point” to make, sure. But if in the process of artmaking it does not expand into something that suggests, something that gives us new questions, something that is spacious enough for wonder, then it isn’t art.

And of the artists I’ve studied and known, I cannot think of one who was striving to merely “deliver a message.” If one thing is consistent in my interviews with, and conversations with, artists of great vision and talent, it their admission that they did not completely know where they were going, nor did they anticipate what the result would be. “The work took on a life of its own,” they say, over and over again.

My favorite definition of “parable” comes from the theologian C.H. Dodd, and it says a lot about what art is:

“Making a point” is different than showing someone something that leaves the mind in [enough] “sufficient doubt” as to actually engage the mind and get us working on something.

As the great Orson Welles said,

Jeffrey, I wanted to thank you for this post. I found you on the web many years ago, when you were first promoting Auralia’s Colors, and I remember you saying similar things then as you do here.

It seems obvious to me now, but it must have been your thoughts back then when I first realized that being a Christian didn’t mean one HAD to write Christian Fiction (i.e., for a Christian audience) out of duty to the Great Commission. Just tell the story. I think you planted something in me, because seeing your book made me wonder if I could do the same. Last year I published my first book: not a Christian fantasy, but a fantasy, plain and simple.

The reason why I stopped by was to say I FINALLY read Auralia’s Colors this week! (Sorry it took me so long to get to it, but it was worth the wait.) You’ve crafted a fantastic story, very original. Your prose is also quite beautiful and poetic, not something I expected but was pleasantly surprised (after reading thousands of pages of Martin). I enjoyed it very much. I am already on the second thread. Just great stuff.

Thanks again.