[This review was originally published at Christianity Today.]

•

If you want to inspire a challenging discussion about art and culture, try this: Watch Martin Scorsese’s excellent 2006 documentary No Direction Home: Bob Dylan, and discuss it. Then, reconvene a week later for a viewing of Todd Haynes’ surreal new movie I’m Not There. Their differing, complimentary portraits of Bob Dylan will give you so much material to ponder and discuss, you won’t know where to begin.

To study Dylan’s career is to ponder provocative questions about poetry, politics, music, politics, celebrity, spirituality, and American history. It is beyond dispute that he’s an artist of skill, imagination, and vision. But he is also as human as the rest of us, a man whose missteps have been almost as spectacular as his successes.

A dictionary full of words have fallen short of describing him. He’s been a rebel, a prophet, a poet … even “Judas.” He’s almost too big for a movie. But Haynes’ film emphasizes the fact that Dylan escapes all attempts to define and explain him. Taking up a few (but only a few) strands of Dylan’s career, Haynes braids them together. It’s a complicated weave of periods, styles, and facets of Dylan’s personality.

Experiencing Haynes’ ambitious vision is a little like trying to tour the Grand Canyon in two hours. The movie’s whirlwind of information and ideas is both exhilarating and ultimately exhausting. Still, how often do we have this problem—a movie that gives us too much of a good thing?

Haynes tracks Dylan’s emergence as a freewheelin’ folk-singer fond of Woody Guthrie; his rise as a political poet of the ’60s; the troubles of his personal life; his flight from exploitation; all the way to recent years, where he’s become something of a recluse and a wanderer, traveling through the backwoods of American music.

Dylan’s career—both onstage and off—has reminded us that poetry can convey what more didactic forms of communication cannot. His genius can be found when we examine what he has written and sung, and how his metaphors grow from—and speak back to—his audience, culture, country, and times. But, contrary to what the American people have believed, that is where it stops. When we look at Dylan himself in hopes of revelation, we’re in trouble, and he knows that.

But poetry is a language that must be learned, and most of those seeking to define, categorize, and exploit the Artist are not fluent in poetry. In fact, Dylan’s songs contain some of his most scathing rebukes, making fools of those who try to pin him down, even as they pat themselves on the back for trying.

To cope with those who would seek to box him in, Dylan has become an exemplary shapeshifter, answering his interrogators with jokes and riddles, always aware that a direct answer — should he ever attempt one — will be misunderstood, unraveled, and remade into a noose. And he devoutly refuses to follow any guidance but the artistic impulse, which is a still, small voice. An artist devoted to his muse is a moving target—a “rolling stone.”

Haynes has no desire to “solve” Dylan. So he casts several actors as differing manifestations of the mystery. These characters resemble Dylan. Haynes never once mentions Dylan’s name, giving each “version” his (or her) own character. Each is a living, breathing metaphor, exposing differing aspects of a complex man. (One of them, in a fictional flourish, even dies of a drug overdose. We’re invited to the autopsy.)

The film begins with Marcus Carl Franklin as Woody, the 11-year-old African-American version of the Artist — no, I’m not making that up. As he confesses to a couple of admiring hobos in a boxcar, “I don’t know who I am most of the time.” It’s as if he’s channeling a who’s-who of American bards and poets, from Whitman to Guthrie, while his own identity remains elusive.

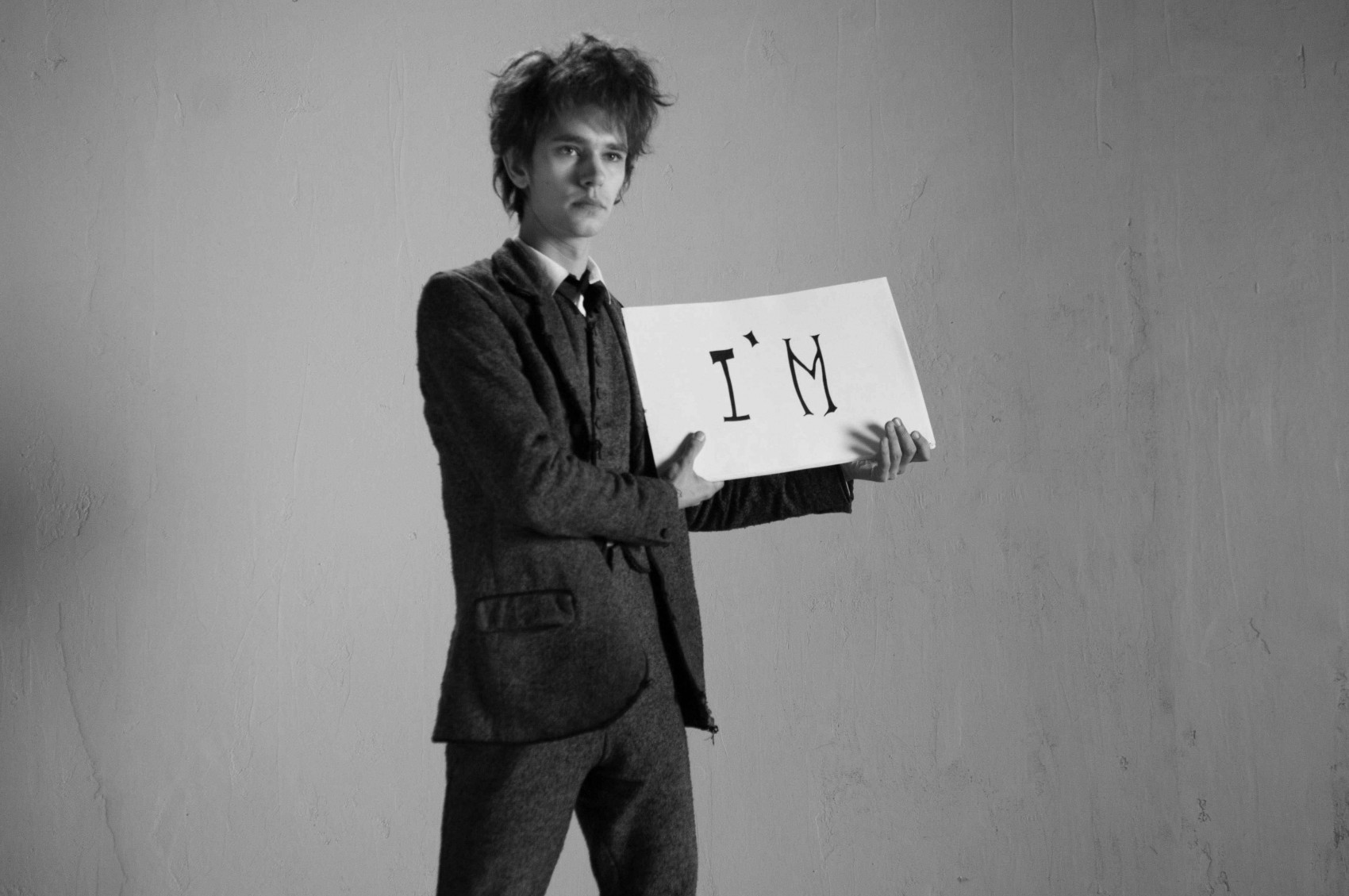

Personifying the Artist cornered by the persistently oblivious reporters, Arthur (Ben Wishaw) answers questions with wry, weary retorts, quoting directly from Dylan’s library of challenging (some would say “cryptic”) interviews.

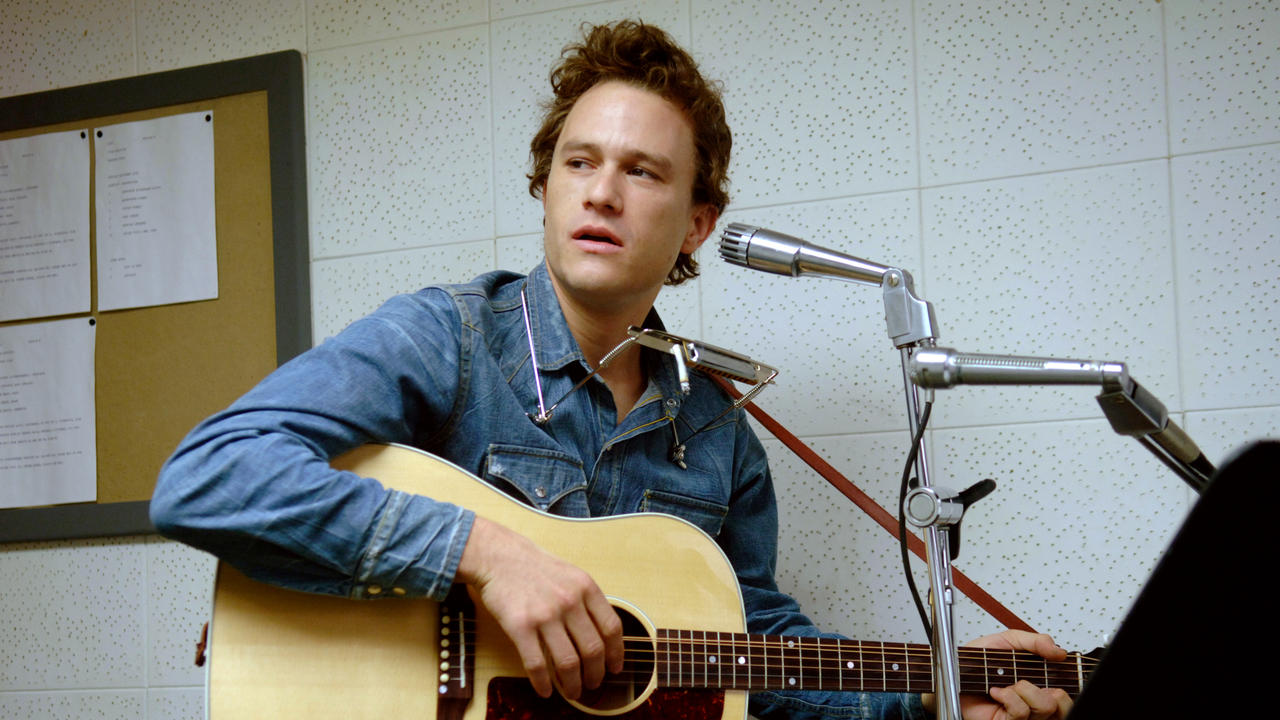

Christian Bale plays Jack Rollins, a rising star in the folk music world, soon to be cursed with the title “Voice of a Generation.” When Jack Rollins opens his mouth to let the vocals of rocker Stephen Malkmus ring out, most viewers will be oblivious to Bale’s perfect lip-synch. It’s too bad Bale’s exceptional performance will be overshadowed by the showier performance that comes next.

Later, Bale will return as the Artist who fled from the spotlight into the comforts of 1970s evangelical Christianity, and became “Pastor John.” But even the church let him down, becoming another stifling community eager to exploit him as a model of musical missionary work. (If any chapter of Dylan’s career gets short shrift here, it’s this one.)

In the film’s most talked-about bit of “stunt casting,” Cate Blanchett plays Jude Quinn, resembling the mid-’60s Dylan. It’s a brilliant move—Blanchett’s uncanny performance shows us how Dylan’s public persona became an extension of his art, full of riddles, metaphor, evasion, and comedy. This is the Dylan of Don’t Look Back, who evolved in ways that upset fans who wanted to claim him as their political or cultural representative.

When Quinn gets onstage at a folk revival, plugs in electric guitars, and growls “I ain’t gonna work on Maggie’s farm no more,” it’s clear that he’s chasing his vision no matter what the cost. The audience, feeling betrayed, hurt, and outraged, walks away convinced that their hero has sold out. One fan staggers away, profoundly observing, “He’s not like he was.”

In one memorable moment, Quinn and Alan Ginsberg (David Cross) clown around in front of a statue of Christ on the cross. But they’re not being sacrilegious. They’re mimicking the ridiculous cries of the masses, who misunderstand Dylan the way Christ’s audience misunderstood him. Elsewhere, in a sequence as surreal as a music video, Quinn sneers and spits out a performance of “Mr. Jones,” staring laser beams into the arrogant, condescending BBC journalist who persecutes him.

Heath Ledger plays Robbie, a singer striving to turn his musical success into a legend-making Hollywood breakthrough. Robbie’s scenes offer interpretations of Dylan’s personal relationships, marriage, fatherhood, and heartbreak. Acting like the heir-apparent to James Dean’s rebel throne, he loses touch with his beloved Claire (Charlotte Gainsbourg), who is also the mother of his children. Ledger is impressive, but Gainsbourg almost steals the movie as the woman who cannot hold on to the locomotive she has married.

Finally, Richard Gere is the reclusive “Mr. B,” a retired Billy the Kid on the run from lawmen with grudges. In this, the most fanciful thread, the Artist retreats from fame and celebrity only to find that the Enemy has grown too powerful, laying waste to the wilderness where he’s been trying to hide. In the town of Halloween—part wild west movie set, part circus—a villainous lawman confronts the Artist again, and he has a familiar face.

I’m Not There also boasts some memorable supporting turns. Julianne Moore plays the equivalent of Joan Baez, hilariously pretentious as she recounts her memories. Bruce Greenwood is brilliant as the manifestations of the Enemy, most of them condescending, arrogant journalists. And David Cross is hilarious as Alan Ginsberg.

Haynes’ kaleidoscopic style packs in so many clever references to Dylan trivia that longtime fans will nod, gasp, and laugh out loud. (Do you know what that tarantula represents?) Those who only know a handful of Dylan songs may wonder what’s fact, what’s fiction, and why it matters. Aesthetically, Haynes references Dylan’s own big screen ventures, like Don’t Look Back and Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, as well as films that Dylan apparently admired, like 8½. Much of the dialogue is drawn straight from interviews, live footage, and Dylan’s own cinematic projects (the good and the bad).

Instead of aiming to please with a soundtrack full of hits, Haynes makes surprising selections from the Dylan catalog. Sure, “Like a Rolling Stone” gets prominent play, but a track from the official Dylan Bootleg collection—”Blind Willie McTell”—brings out beauty and soul in one of the film’s more moving passages. Other masterful songs like “It’s Not Dark Yet” and “Man in the Long Black Coat” are used more like traditional soundtrack music, more for mood than meaning.

It feels like the movie toward which Haynes has been building all along. Haynes’ first movie project was co-authoring Superstar, a Super-8 version of the Karen Carpenter story starring Barbie dolls. He also made Velvet Goldmine, both a tribute to, and an evisceration of, the glam-rock era, with Jonathan Rhys Meyers as a David Bowie figure. He also proved his talent for resurrecting bygone eras with the remarkable homage to the 1950s films of Douglas Sirk, Far From Heaven, which was so obsessed with replicating Sirk’s style that it toed the line of satire.

And yet, it may be that Haynes released the film too early. There’s a 90-minute masterpiece in this film, waiting for an editor to find it. Had Haynes been braver and cut some of the good stuff to make the best parts even better, we would have walked out overwhelmed and delighted. But at 135 minutes, I’m Not There makes viewers feel like they’re being sent back to the table for seconds, thirds, and more, long after they had their fill. Near the end, we’re left guessing just which Dylan will have the last word.

But in the larger scheme of things, the last word on Dylan will never be spoken. And we can be grateful for that.